Curriculum Vitae

2021-08-16 00:00:00 -0700

[Download Curriculum Vitae 2021]

Education

present: PhD Candidate, Computational Media, University of California, Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA.

2013: MFA Arts and Technology, University of Texas at Dallas, Richardson, TX.

2006: BFA Digital Media, Kendall College of Art and Design of Ferris State University, Grand Rapids, MI

Teaching

- Summer 2021 Instructor, Teaching Fellow, Game Development Experience. (online)

-

Summer 2019 Instructor, Associate In Computational Media, Game Development Experience.

- Spring 2021 Teaching Assistant, Game Design Studio III. (online)

- Winter 2021 Teaching Assistant, Game Design Studio II. (online)

- Fall 2020 Teaching Assistant, Game Design Studio I. (online)

- Summer 2020 Teaching Assistant, Game Technologies. (online)

- Spring 2020 Teaching Assistant, Interactive Storytelling. (online)

- Winter 2020 Teaching Assistant, Data Structures for Interactive Media.

- Fall 2019 Teaching Assistant, Generative Design.

- Fall 2018 Teaching Assistant, Visual Communication and Interaction Design.

- Fall 2017 Teaching Assistant, Procedural Content Generation (Game Design Practicum).

Peer-Reviewed Publications

Journal Articles

Karth, Isaac and Adam Marshall Smith (2021). “WaveFunctionCollapse: Content Generation via Constraint Solving and Machine Learning”. In: IEEE Transactions on Games. doi: 10.1109/TG.2021.3076368.

Karth, Isaac (2019). “Preliminary poetics of procedural generation in games”. In: Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association. doi: https://doi.org/10.26503/todigra.v4i3.106.

Conference Proceedings

Karth, Isaac (July 2018). “Preliminary Poetics of Procedural Generation in Games”. In: DiGRA ’18 - Proceedings of the 2018 DiGRA International Conference: The Game is the Message. Turin, Italy: DiGRA. url: http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/DIGRA_2018_paper_166.pdf.

Karth, Isaac (2014). “Ergodic Agency: How Play Manifests Understanding”. In: Engaging with Videogames: Play, Theory and Practice. Ed. by Dawn Stobbart and Monica Evans. Inter-Disciplinary Press, pp. 205–216. isbn: 978-1-84888-295-9.

Workshop Proceedings

Karth, Isaac and Adam M. Smith (2019). “Addressing the Fundamental Tension of PCGML with Discriminative Learning”. In: Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games. FDG ’19. San Luis Obispo, California: ACM, 89:1–89:9. isbn: 978-1-4503-7217-6. doi: 10.1145/3337722.3341845. url: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/3337722.3341845.

Kreminski, Max, Isaac Karth, and Noah Wardrip-Fruin (2019). “Generators that Read”. In: Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games. ACM.

Karth, Isaac and Adam M. Smith (2017). “WaveFunctionCollapse is Constraint Solving in the Wild”. In: Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games. 14-17 August, FDG ’17. Hyannis, Massachusetts: ACM, 68:1–68:10. isbn: 978-1-4503-5319-9. doi: 10.1145/3102071.3110566. url: http://doi.acm.org/10.1145/3102071.3110566.

Posters

Isaac Karth, Batu Aytemiz, Ross Mawhorter, and Adam M. Smith (2021). “Neurosymbolic Map Generation with VQ-VAE and WFC”. In: Proceedings of 16th International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games.

Aytemiz, Batu, Karth, Isaac, Jesse Harder, Adam M Smith, and Jim Whitehead (2018). “Talin: A Framework for Dynamic Tutorials Based on the Skill Atoms Theory”. In: Fourteenth Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment Conference.

Demos

Isaac Karth, Tamara Duplantis, Max Kreminski, Sachita Kashyap, Vijaya Kukutla, Anika Mittal, Harvin Park, and Adam M. Smith (2021). “Generating Playable RPG ROMs forthe Game Boy”. In: Games and Demonstrations at Foundations of Digital Games 2021 (Best Game/Demo Award).

Awards, Honors, Fellowships

2021 Summer Research Grant, UCSC Computational Media Department.

2020 CITL Graduate Pedagogy Fellow in Computational Media, UCSC.

Invited Talks

Karth, Isaac (2017). Worldbuilding and Procedural Generation. Invited Talk. Dakota State University. November 9, 2017.

Service to Profession

- 2020 Workshop Co-Organizer, PCG2020 (11th Workshop on Procedural Content Generation).

- 2021 Program Committee (Research Track), AIIDE-21 (17th AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Interactive Digital Entertainment).

- 2021 Program Committee, EXAG 2021 (Experimental AI in Games 2021).

- 2021 Program Committee, PCG 2021 (12th Workshop on Procedural Content Generation).

- 2021 Program Committee, IEEE COG 2021 (2021 IEEE Conference on Games).

- 2020 Program Committee, EXAG 2020 (Experimental AI in Games Workshop 2020).

- 2020 Program Committee, ICCC’20 (International Conference on Computational Creativity).

- 2019 Program Committee, EXAG 2019 (Experimental AI in Games 2019).

- 2018 Program Committee, PCG 2018 (9th Workshop on Procedural Content Generation).

Nonacademic Work

2013–2017 Freelance Technical Artist, Isaac Karth Interactive, Raleigh, NC.

2007–2010 Media Specialist, Panacore Corporation, Odessa, TX.

Sumer

2020-04-09 00:00:00 -0700

One of the early videogames made for an educational purpose is The Sumerian Game, running on a time-shared IBM mainframe 7090 in 1964. The educational and entertainment value of the game owes a lot to Mabel Addis’s work on the design and writing. Sadly, the original program is lost–but like many other early computer games, the description of the game inspired other programmers to make their own implementations.

In this case, the description of the game lead to Doug Dyment’s DEC implementation, King of Sumeria, a stripped-down 4kb version that ran on a PBP-8 in 1969. This eventually influenced David Ahi’s BASIC version, Hamuarbi [sic], in 1973.

In 2020, I was looking around for something to implement in the narrative scripting language Ink. I’d encountered the BASIC version previously, but reading an article about The Sumerian Game inspired me to create a version that brought it back a little closer to the original’s narrative focus.

Sumer is available to play at https://ikarth.itch.io/sumer.

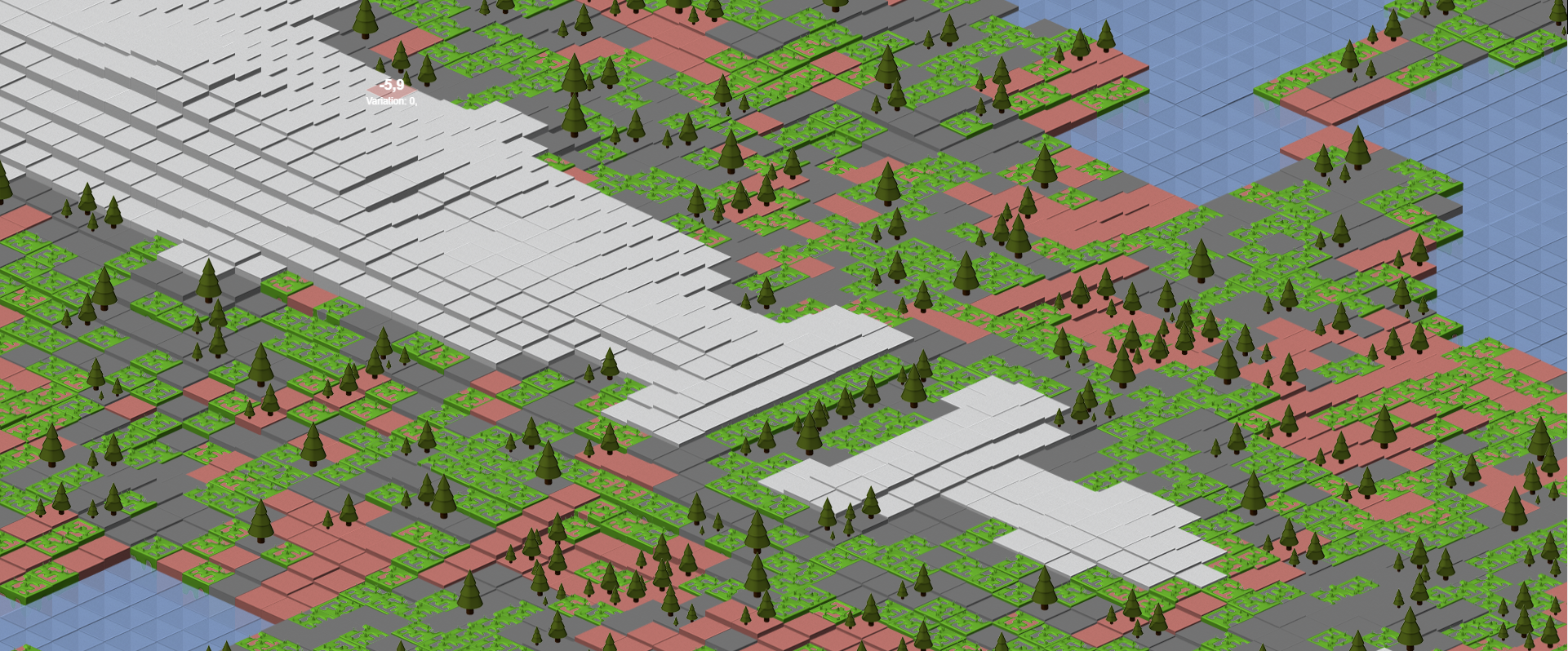

Terrain Generation from Noise

2017-11-07 00:00:00 -0800

For this project I helped develop a series of student assignments. The significance of this work is not primarily in the software itself but rather in the educational purpose behind it. These assignments were developed with Adam Smith as part of the Generative Design class at UCSC. Each project was designed to act as a framework for students to build their own solutions on top of while allowing them to concentrate on the design and programming related to the assignment rather than low-level graphics.

Building a generative system as a demonstration for educational purposes involves additional challenges. Because the code serves as a basis for the students’ own projects it needs to have enough detail to be instructive while not pre-defining the answer. The students were provided with a JavaScript template that uses p5.js for displaying graphics, which they had a chance to familiarize themselves with in an earlier assignment.

The Generative Design class typically has students from both the Computer Science: Game Design degree program and the Art, Games and Playable Media degree program, the assignment design needed to address the needs of both art-focused and programming-focused students. In order to guide the students to consider the aesthetic questions involved in designing the generator, we asked them to begin with an inspiring image, to anchor their design.

The learning goals for this particular assignment were for the students to become familiar with dealing with generating an infinite object, controlling deterministic randomness through a hash-value seed, and dealing with stateful interaction with an infinite object, important concepts for constructing large-scale procedural generation systems.

Live Demo

In addition to the base code that handled basic graphical operation and interaction, we provided a simple example for the students to use as a basis for their own code.

The assignment was project 2, hence the ‘p2’ prefix on all of the API functions. Several of the API functions handled different stages of the execution; for example p2_preload() and p2_setup() were intended for the students to add their own initialization code.

On a technical level, creating deterministic algorithms is important for getting repeatable results in generative design and is the basis of many other techniques. This is typically done through the use of a pseudo random number generator, starting from a fixed seed. However, there are drawbacks to this approach. Most notably, to have the same outcome the random rolls need to happen in the exact same order.

Therefore, one pedagogical purpose of the assignment was to introduce the idea of hashing. A hash function converts data into a string of numbers, where inputting the same data always results in an identical hash, and different data has a different hash, with minimal collisions. In addition to its use for generative design, hashing is also the basis for modern cryptography. We provided the xxHash hashing algorithm to students.

function p2_worldKeyChanged(key) {

worldSeed = XXH.h32(key, 0);

noiseSeed(worldSeed);

randomSeed(worldSeed);

}

The p2_worldKeyChanged(key) function provided a simple starting point for one way to approach using the hashing function, initializing the Processing (pseudo) random number generators with a seed derived from a hash. The p2_drawTile(i,j) function demonstrated how to use the hash directly, bypassing the RNG altogether:

if (XXH.h32("tile:" + [i, j], worldSeed) % 4 == 0) {

fill(240, 200);

} else {

fill(255, 200);

}

One part of the rubric for the assignment was that the tiles being generated had to show variation in space - in other words, as we scroll the camera around, we should see a variety of different things. In effect, the p2_drawTile(i,j) function needs to be able to produce many different results, have them change based on the coordinates passed to it (in an effectively unbounded space), and always return the exact same result.

This gave the students the opportunity to address the problem of creating a generative system that needed more information than could be supplied by hand, which required them to implement generative solutions. It also served as practice for creating data structures that can handle a finite but unbounded amount of information. Because the tiles are generated just-in-time, the students have to learn how to incorporate the secondary data structure (by default, the list of clicks) into the generative process.

The students were also given the suggestion that they could incorporate time into their worlds, using the millis() time functions to drive changes.

Subsequent iterations of the class have used the glitch.me platform. This opened up opportunities for collaboration between students, with the intent of fostering peer-discussion and knowledge sharing. We encouraged code-sharing, with the requirement that any code not written by the student had to be explicitly cited in comments. Together with the requirement for using an inspiring image and writing an artist statement, this minimized incentives for academic dishonesty.

The assignment was also revised to focus on quantity over (explicit) quality, with the reasoning that students who pushed themselves to make three generators (each different from the others) would gain more practice at building generators and have a deeper learning experience.

Scoring Rubric

[3 pts] Infinity: The world (or whatever thing it is) extends infinitely in at least one direction. Different takes on this might show different things: infinite terrain, infinite carpet, infinite table surface, etc.

[3 pts] Variation in Space: There is interesting variation in tiles to be seen (both without moving the camera and by moving the camera from one region to another). Explore different kinds of spatial variation in your different generators.

[3 pts] Variation in Key: There is interesting variation in tiles to be seen by changing the world key, and variations can be restored by entering a previous key. Use the key to control different aspects in different generators.

[3 pts] Signs of Life: The world responds to audience clicks and/or the passage of time in an interesting way that keeps this from simply being a static scrollable picture.

The three generators also helped overcome one of the original weaknesses of the assignment: students sticking too close to the example generator and not exploring the possibilities. A key benefit of the assignment comes from the students realizing the multiple ways to approach the problem, which the multiple-generator version helped facilitate.

For future iterations of the assignment, one improvement might be to give a deeper introduction to ways that the tile generation can be combined with other generators. For example, introducing the idea of biomes - regions of the map that use a different set of parameters - or having variation based on distance to a nearby landmark. Additionally, revisiting the assignment once additional concepts are introduced would give them the opportunity to incorporate new techniques that build on their previous knowledge (such as implementing Voronoi-based regions in an unbounded space).

2017 Version: https://ikarth.itch.io/terrain-generation-from-noise

2019 Version: https://lilac-market.glitch.me/

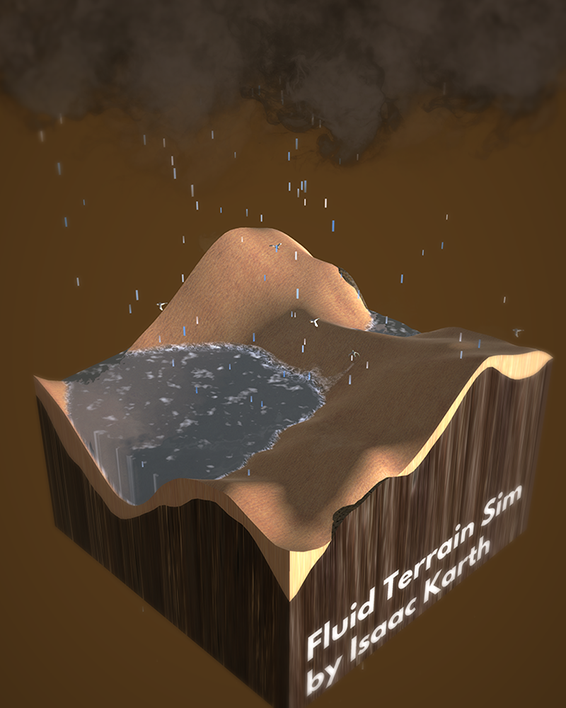

Ocean Terrain Generator

2016-12-01 00:00:00 -0800

The Ocean Terrain Generator was created for ProcJam 2016, and uses a stack of fluid generators to simulate erosion and water on a generated terrain. Rainfall and evaporation are explictly visualized with clouds, sunbeams, rain, and mist.

The interactive app can be downloaded on itch.io.

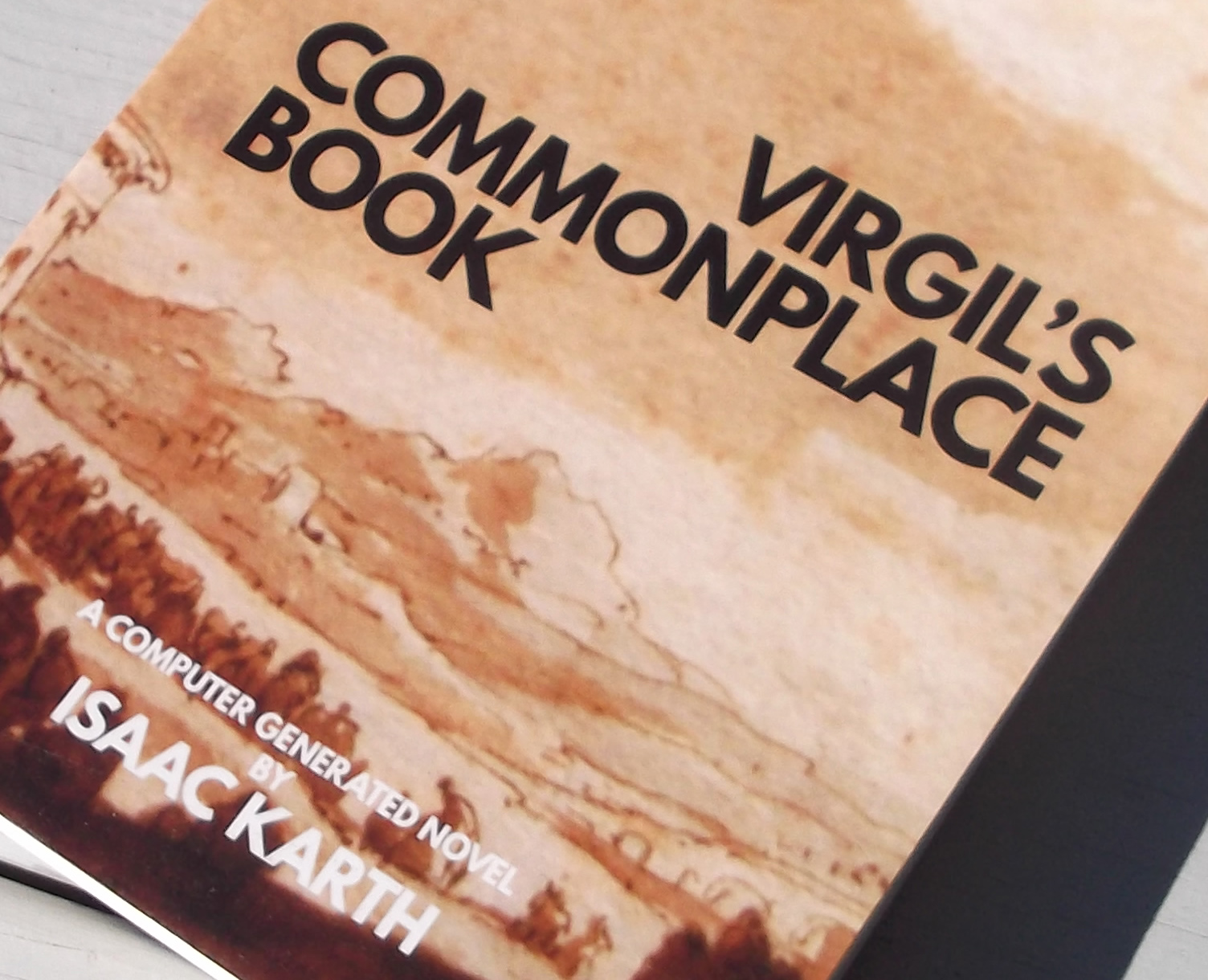

Virgil's Commonplace Book

2015-12-01 00:00:00 -0800

Introduction

Virgil’s Commonplace Book is a computer-generated travel novel set in the Roman Empire. It was originally created as a part of National Novel Generation Month (NaNoGenMo). There’s also a related Twitter bot, @erat_viator.

Like all of my NaNoGenMo projects, the source code is on GitHub. The novel itself can be downloaded as well.

NaNoGenMo

National Novel Generation Month started in 2013 with a tweet by Darius Kazemi: “Hey, who wants to join me in NaNoGenMo: spend the month writing code that generates a 50k word novel, share the novel & the code at the end”. Riffing off of the idea of National Novel Writing Month, instead of writing a novel in a month, programmer-artists have made hundreds of novel generators since the event started.

Writing a novel generator is a somewhat niche practice, but prior to 2013 most text generation projects didn’t attempt anything close to the length of these books. The state of the art has advanced considerably over the course of the event’s existence. Adopting the NaNoWriMo definition of 50,000 words, NaNoGenMo is intentionally expansive in what constitutes a novel, and many of the generated novels are more interesting as conceptual art than as page-turners. But some of the novels can be enjoyable reads even apart from their generative context. However, in my estimation, the most successful generated novels require a strong motivating idea that is visibly realized on the page.

The Novel

The copy of this book that you see here is just one possible version of it: the novel generator is capable of creating a vast number of variations of it, some of which explore very different parts of the Roman Empire. Every version also has some commonalities: the same character, the same theme, the same Roman literature to draw from. This coincides with my philosophy of procedural generation: rather than abandoning the result to random chaos, I believe that anchoring the generator with a clear concept provides an inroad for the reader. The reader can use a starting point like this to gradually build out an understanding of the generator. Particularly a balanced generator with enough order to leave legible patterns and enough chaos to surprise us.

The pattern of this novel is simple enough, at the largest scale: Virgil begins in Rome, looks at the cities to which he can travel, and chooses one. He prefers to visit cities that he has not been to before. When he reaches a city, he finds something that has been written about it, or about the land nearby, and includes it in his commonplace book.

I had little control over which passages were chosen or which cities were visited. By happy coincidence, the first chapter corresponded to the path that the generator’s counterpart twitterbot is travelling on its similar errand, and thereafter I left the random seeds alone and let the chips fall where they may.

I haven’t read all of the book yet, myself: this is intentional. One of my inspirations was a bot that posts random museum artifacts and the bot that follows it that invents opinions about the art. I’ve learned little bits of history from it that I’d otherwise never have encountered. This novel is, therefore, closer to browsing a library than to searching the internet. There are things in here that I never would have read, and parts of the Roman Empire I never would have learned the geography of if I hadn’t worked on this project.

The Publication

Despite participating in National Novel Generation Month quite a few times, and this is the first time I feel that I’ve satisfactorily achieved the Apollonian-Dionysian balance that I think good procedural generation needs. Not that I lack ideas for improving it: there are more sources of historical data to draw from, and on the last day of November I had an idea that would allow a plot arc to be incorporated. You can plot Virgil’s path on a map, if you like: I’d have liked to have included one in the book, but it wasn’t in the cards for this edition.

While the generator can create endless variations of the novel, each particular copy is fixed. When you read the book, your experience of it is fixed in time. Even if the pages change before or after, the book you read in the moment is singular and unchanging. Future versions of this book may, in fact, be quite different. This, therefore, is the November 30th, 2015 edition, with a couple of formatting tweaks for printing, but no changes to the text itself.

A Commonplace Book

It has long been a common practice to incorporate the works of earlier writers into new books. Indeed, many commonplace books consist of nothing but quotations and similar notes. We have many surviving examples from the Roman Empire, such as Aulus Gellius’ Attic Nights. These texts were not always attributed to the original source. Lacking the modern concept of plagiarism (and our post-printing-press system of uniform citations) writers sometimes come off as careless to modern sensibilities. Quotes could be paraphrased and rather vague citations were the norm. Indeed, some authors committed a kind of reverse plagiarism, pseudepigraphically attributing their work to an earlier, more famous author.

In a way, this reuse is fortunate: many texts from the Classical period only exist in fragments quoted in other documents. Some works survive in epitome, distilled versions that summarized the text; for others we have fragments that later writers quoted or abridged as they wrote their compilations.

Artistic Movements

Artists, of course, have been far looser with their borrowings than writers of mere facts, placing the present work solidly within a long tradition. The closest literary antecedents of NaNoGenMo–Dada and Oulipo–have often explored similar sampling approaches. Kathryn Hume has suggested that technical constraints have led NaNoGenMo to “align itself with poetics of recontextualization and reassembly.”

NaNoGenMo has included other approaches, such as the concrete poetry in thricedotted’s The Seeker, or the way structurally-plotted works like Hannah and The Twelve-Disk Tower of Hanoi evoke the chessboard constraints of Life a User’s Manual or Through the Looking Glass. But there is an undeniable strand of appropriation as we teach our machines to imitate their human creators. Still, that’s no reason to neglect giving credit, so this book attempts to cite the sources for the texts it borrows.

Serendipity in Procedural Generation

In this work, that deliberate borrowing is the intent. Unlike an age of precious codices, the information age is a time of entirely too much to read. Search engines can find anything you ask for but, like a fairy-tale mirror, can only answer the questions you know enough to ask in the first place. The serendipity of browsing through a library is lost. Extracting the stories and arranging them in a new pattern presents a new angle. Rather than an exhaustive view of the forest, it picks out one or two trees you might have otherwise overlooked.

Of the many motivations for using procedural content generation, serendipity has gotten less attention than efficiency or scale but perhaps has a longer aesthetic history: the Dadaists use of cut-ups, the discovery of unexpected juxtapositions in Raymond Llull’s volvelles, and various practices of divination, especially for our purposes, bibliomancy. As Jessen Lee Kelly points out, the Renaissance saw aleatory divination via both specially-designed lottery books and through randomly selecting a line from an existing text, such as the protagonists Rabelais’s The Life of Gargantua and of Pantagruel turning to Homer and Virgil to predict the future.

The present work has elements of both the way that lottery books were organized by subject and the use of classical texts. It draws on the Perseus Digital Library’s public API to index passages by their metainformation, so as the novel wanders around the Mediterranean landscape it chooses text that relates to the local history and mythology. But simultaneously, it is drawing from classical texts, the operation of the machinery acting as a kind of Virgilian lots.

The Protagonist

I chose Virgil as the protagonist for three reasons: first, his works are among the source texts in the Perseus Digital Library used for much of the text here. His Aeneid builds on earlier traditions, recast in a founding epic for a new age: appropriate for a work themed around appropriation and reuse in this new information age. This would not be enough to recommend him on its own: there are other authors whose works were much closer to the kind of copying and summarizing going on here. And The Golden Ass by Apuleius, one of the earliest surviving novels, is closer in form to the travel tale that structures this generated novel.

But there was also a tradition that linked Virgil and his poetry with magic and prophecy. It was no accident that Dante chose Virgil to be his guide through the Inferno. His memory is haunted by that touch of magic, a magic intimately linked with words and poetry. And, as Jeff Howard has pointed out in Game Magic: A Designer’s Guide to Magic Systems in Theory and Practice, programming is a form of magic. A magician-protagonist is entirely appropriate. Lastly, that tradition of magic led the much-neglected Avram Davidson to pen a novel with Vergil Magus as the magician-protagonist. My own pseudo-Virgil is a humble tribute to Davidson’s protagonist, a magician-turned-machine-homunculus librarian of forgotten texts.

Citations

Gramazio, Holly, and Sophie Sampson. “The History of Text Generation.” Matheson Marcault, 15 Dec. 2015, mathesonmarcault.com/index.php/2015/12/15/randomly-generated-title-goes-here/.

Howard, Jeff. “Game Magic: A Designer’s Guide to Magic Systems in Theory and Practice.” 2014. A K Peters/CRC Press. https://doi.org/10.1201/b16848

Hume, Kathryn. “NaNoGenMo: Dada 2.0.” 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2020, from https://arcade.stanford.edu/blogs/nanogenmo-dada-20.

Karr, Suzanne. “Constructions both Sacred and Profane: Serpents, Angels, and Pointing Fingers in Renaissance Books with Moving Parts.” The Yale University Library Gazette 78, no. 3/4 (2004): 101-27. Accessed December 14, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40859568.

Kelly, J. L. (2011). Renaissance Futures: Chance, Prediction, and Play in Northern European Visual Culture, c. 1480-1550. UC Berkeley. ProQuest ID: Kelly_berkeley_0028E_11817. Merritt ID: ark:/13030/m5df9vr6. Retrieved from https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6r20h5s3

Invisible Cities

2015-07-01 00:00:00 -0700

Invisible Cities from Isaac Karth on Vimeo.

3D Modeling and Rendering

2014-04-01 00:00:00 -0700

Nor Does Lightning Travel In A Straight Line

2011-05-01 00:00:00 -0700

A short film celebrating the work of Benoît Mandelbrot. Every image in film directly reflects an example Benoît Mandelbrot used to explain fractals and the human anticipation of their mathematical complexity. The editing is structured to follow a fractal pattern and is intended to be self-affine over three levels.